#5 "Personal Hell in the Harlem Renaissance: Gladys Bentley's Sartorial Responses to Respectability"

Gladys Bentley's trad-wife era :/

If you thought I forgot about posting my thesis, you were right and wrong. With Jupiter in Cancer, I feel like life is all about expansion and abundance. At least, that’s what the astrologers say. I’ve been trying to como se dice “lock in.” I mentioned to someone, my thesis is kind of like my brat album. Apparently, it’s a thing that Charli XCX is still touring and releasing music videos for her album a year later. I do think that art is eternal and living. There’s always a new way to interpret what’s been done before. That’s what Audre Lorde says, “For there are no new ideas. There are only new ways of making them felt, of examining what our ideas really mean…”

I’ve posted two TikToks about Gladys Bentley and they have been incredibly received on TikTok. (That may be the first time those words have been written). It’s shocking actually. After having been cyberbullied for how I choose to look, I thought positive TikTok feedback en masse was never possible. However, the lesbian community showed up for me in terms of TikTok metrics.

If you are new here and are wondering well, where’s the first part of the award-winning thesis you keep mentioning? Here are parts one through four of said thesis:

#1 "Personal Hell in the Harlem Renaissance: Gladys Bentley's Sartorial Responses to Respectability"

#2 "Personal Hell in the Harlem Renaissance: Gladys Bentley's Sartorial Responses to Respectability"

#3 "Personal Hell in the Harlem Renaissance: Gladys Bentley's Sartorial Responses to Respectability"

#4 "Personal Hell in the Harlem Renaissance: Gladys Bentley's Sartorial Responses to Respectability"

Now, you are caught up, so here’s #5:

RETURNING “HOME” TO WOMANHOOD

At the conclusion of World War II, men were able to return to their jobs and women were pushed back into the home. After taking on jobs typically done by men to support the war effort, women were encouraged to reaffirm their femininity by fulfilling the domestic role they once had. For Bentley, a Black woman, her roles were not clearly defined between man and woman. Black women were working outside the home even in times of peace. Black feminist scholar Angela Davis writes, “She was not sheltered or protected; she would not remain oblivious to the desperate struggle for existence unfolding outside the ‘home.’ She was also there in the fields, alongside the man, toiling under the lash from sun-up to sun-down.”1 The legacy of the Black woman in America has been to almost consistently work outside the home despite her femaleness that should have shielded her from that. Davis continues, “It was the woman who was charged with keeping the “home” in order. This role was dictated by the male supremacist ideology of white society in America; it was also woven into the patriarchal traditions of Africa. As her biological destiny, the woman bore the fruits of procreation; as her social destiny, she cooked, sewed, washed, cleaned house, raised the children.”2 The reinscription of traditional patriarchal values at the conclusion of the war, encouraged Bentley to take on her “natural” role as a woman.

Bentley’s aspiration to femininity in the postwar era reflects the ideas of Black womanhood presented by Elise Johnson McDougald, a Black female thinker during the Harlem Renaissance who supported women’s concern being with the home. She describes four class of Black women using the following characteristics:

First, comes a very small leisure group–the wives and daughters of men who are in business, in the professions and a few well-paid personal service occupations. Second, a most active and progressive group, the women in business and the professions. Third, the many women in the trades and industry. Fourth, a group weighty in numbers struggling on in domestic service, with an even less fortunate fringe of casual workers, fluctuating with the economic temper of the time.3

She welcomes the first group because the women are free to take care of the home and are “touched only faintly by their race’s hardship.”4 McDougald privileges the first group over the fourth group, placing this group as aspirational in contrast to the fourth classification that is described as having sex irregularities and immorality because of socioeconomic conditions, not racial conditions. She goes on to state, “There is no proof of inherent weakness in the ethnic group.”5

McDougald is well-aligned with the Harlem Renaissance’s mission of improving conditions for Black people through proving humanity through arts and letters. The Harlem Renaissance was exclusive and Black people of a lower social class were not always welcome. It was thought that to improve the conditions of Black people, one should hide any aspects that could be a cause for shame. McDougald uses the example of illegitimate children. Having children out of wedlock was discouraged because pathology around the Black family structure was a huge concern at the time. However, the push to be a moral citizen did not only exist within Harlem.

The Wales Padlock law decreed that “theaters would be padlocked for one year should the owners refuse to close a show that a jury believed ‘would tend to the corruption of youth or others.’”6 This law was part of an effort by John S. Sumner, head of the New York Society for the Suppression of the Vice.7 Censorship and police raids were popular during the times of the Harlem Renaissance and reflect a clear effort to censor the Harlem Renaissance acts that featured content deemed sexually immoral which included homosexuality. Theater and art critics criticized Bentley’s suggestive lyrics and the people who liked them. By 1934, the Wales Padlock law had been invoked at King’s Terrace nightclub and Bentley had to move her act. While Gladys Bentley was incredibly popular, her popularity had its consequences. She, like many musicians,adjusted her act to be more profitable. This came at the expense of no longer playing the piano and cleaning up some of her content.

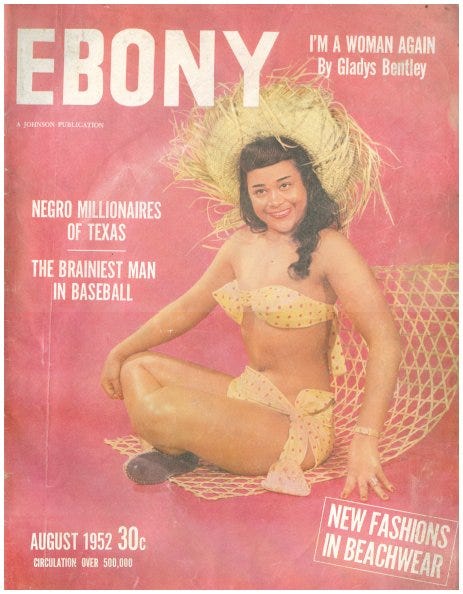

In her personal essay in Ebony Magazine, Bentley meticulously combs through her mistakes and admits that she had been immoral. Bentley’s essay is more of a religious testimony as it includes heavy religious imagery and she concludes by saying she wants to encourage young people to stay on “the path of righteousness” and hopes this will provide redemption for her sins.8 Bentley writes, “I was a big, successful star–and sad, lonely person–until the miracle happened and I became a woman again.”9 The use of the word “miracle” here creates a Christian association. Her miracle comes in the form of “the love and tenderness, the true devotion of a man who loved me unselfishly and whose love I could return.”10 As she begins to describe the man we later know as “Don,”there’s a parallel between him and Jesus Christ who is often defined as unconditionally loving and Christians are able to reciprocate their love by proceeding down the “right” path and encouraging others to do the same. Bentley is very clear that she “want[s] to help others who are trapped in its dark recesses by telling [her] story.”11 After meeting and getting to know Don, she realizes she was afraid of being hurt again. For affirmation she picks up her “teachings of Unity” book and is informed “You are feeling very upset during this cycle. It’s because you are leaving God out of this union, but you must remember God is above all things.”12 Bentley does not explain how she got into the teaching of Unity, but it is known that Bentley was studying to be a Christian minister in the years leading up to her death in 1960, eight years after “I Am a Woman Again” was published.

As Bentley writes she discusses how she was an unwanted child and how that led her to experience sexual inversion. Her mother wanted a boy and she made that very clear in Bentley’s life. She hated her younger brothers and wrote“I suppose the reason was that they were admired while I was scorned.”13 Adopting masculine behaviours was part of Bentley’s pursuit of admiration. Her first steady piano gig began with a similar situation. The Mad House on 133rd Street was in need of a pianist after and intended to fill the position with a boy, but Bentley convinced the owner to give her a chance and she began her career. The problems that Bentley faced as a lesbian are not from conditions simply exclusive to her but wider patriarchal society. It’s commonplace for mothers to prefer boys because they are “less trouble” and for male artists to be privileged over female artists in the music industry. As she sought out admiration, religious belief and romantic desire coincide although not entirely separate and Bentley experiences compulsory heterosexuality.14 In order for Bentley to embrace heterosexuality and her new found romance she must become a woman again.To do this, she visits her physician. She is informed that her sex organs are“infantile” and she is prescribed female hormones to overcome the male hormones. Bentley writes, “The treatment is expensive but worth every penny it costs. Then I was ready to marry him.”15 The process of injecting female hormones to become a woman, despite her being reminded her whole life that she was not a boy, reinforces the idea that lesbians behaviors she exhibited are not the behaviors of a healthy woman and is closely tied to race science.

The medical custom of examining the homosexual body for difference emerged in the nineteenth century, pioneered by German scientists and followed closely by English and American scientists. Sexology, what these scientists studied, had the goal of documenting “abnormalities” in a scientific not judicial method.16 To note these differences, sexologists were able to draw on the work of comparative anatomists who sought to prove Black bodies as fundamentally abnormal and different. Gladys Bentley’s position as a Black female homosexual exposed her to both “sides” of the pathology of difference. Bentley and her doctor leaned into the conceptions of homosexuality as an anatomical difference. However this theory breaks down as lesbians and Black women were, according to sexologists, expected to have an “abnormally large clitoris.” In Bentley’s essay, she does not specify the details of her diagnosis, but one can infer that “infantile sex organs” is not compatible with “abnormally large clitoris” continuing to place Bentley in the third sex that was seen as not entirely masculine and not entirely feminine.

Because of her lesbianism, masculine behavior, and style represented an excess of masculinity, as women are not “supposed to” be masculine. This presents a theme of excess that is evident throughout her essay. She had an excess of male hormones, an excess of weight, an excess of money, and an excess of sexuality. Because of this excess, Bentley is extremely paired down in her presentation and essay to emphasize that she was on the wrong path. She takes upon the self-flagellation popular within Christianity and publicly asks for forgiveness. Bentley writes, “I have strayed far from the social norm and because I have been a victim of my own sins, I cannot but vehemently condemn and denounce those who defend deviation.”17 Bentley’s intense feelings of isolation led her to pursue Christian womanhood.

Roles for women in society were extremely limited, since Bentley hoped to be the minister of a congregation, she chose to engage a desexualized womanhood. Maria Woodworth-Etter, a twentieth century revivalist preacher was known for her plain clothing. She shied away from extravagant styles, usually found in a loose-fitting white dress of an ankle length.18 Preaching has been a traditionally masculine role, so Woodwoorth-Etter feminized preaching by taking the role of mother to her congregation. She took care not to accentuate her bust or waist. Bentley’s previous years in Harlem were highly sexualized in part because of her lyrics and because she chose to make her sexual preferences visible through her dress. She describes those times as “unhappy,” “lonely,” and“restless” ; after her miracle she is happily married and “a woman again.”19 She writes, “Don brought me happiness, not only the happiness which existed during our marriage, but the joy of knowing that, after all, I was as much a woman as any other woman in the world.”20 Through taking on heterosexuality, Bentley was able to reaffirm her individual womanhood. This parallels McDougald’s earlier argument that the most pleasing group of Black women is the housewives who are sheltered from racism through homemaking. In both instances, the oppression that masculinizes Black women whether through sexist views of girls or patriarchal values that encourage Black women to manage the domestic sphere does not disappear but continues to be enforced on women who choose not to conform.

Bentley in her photographs doesn’t take any suggestive poses or dress in feminine attire that could be seen as immodest or tempting. This too is an example of Bentley embracing a desexualized womanhood. With knowledge of the rise in conservatism and domesticized gender roles, it is easy to assume that Bentley’s modesty is only the result of the society she lived within. However, the cover of Ebony Magazine August 1952 features a lightskin, female model sitting on a beach chair in a yellow and pink bikini. As Bentley’s essay is featured in this same issue, we know that it wasn’t off limits for women to show skin, but Bentley was older than the model and had different aims with her portraiture. Instead of drawing attention to her physical feminine qualities, she draws upon conceptual feminine qualities such as preparing to make her husband comfortable in the photos captioned “Turning back cover of bed” and “Taste-testing dinner”. Part of Bentley’s self-critique was that she resisted the love of a man, so her photos show her taking on a passive role. Contributing to her passive appearance on camera, she only looks at the camera one time in the selection of photos produced for her essay.

Angela Davis, “Reflections on the Black Woman’s Role in the Community of Slaves, ” in The Black Scholar 3, no. 4 (1971): 5, https://doi.org/10.1080/00064246.1981.11414214.

Davis, 5.

Elise Johnson McDougald, “The Task of Negro Womanhood, ” in The New Negro: Voices of the Harlem Renaissance, ed. Alain Locke (Touchstone, 1925), 370.

McDougald, 370.

McDougald, 379.

Wilson, 34.

Wilson, 32.

Bentley, Ebony.

Bentley, Ebony.

Bentley, Ebony.

Bentley, Ebony.

Bentley, Ebony.

Bentley, Ebony.

Adrienne Rich, “Compulsory Heterosexuality and Lesbian Existence” in Journal of Women’s History 15 no. 3 (2003), 11-48, https://doi.org/10.1353/jowh.2003.0079.

Bentley, Ebony.

Siobhan B. Somerville, Queering the Color Line: Race and the Invention of Homosexuality in American Culture, (Duke University Press, 2000), 18.

Bentley, Ebony.

Payne, Leah. “‘Pants Don't Make Preachers’: Fashion and Gender Construction in Late-Nineteenth-and Early-Twentieth-Century American Revivalism.” In Fashion Theory: A Journal of Dress, Body, and Culture 19, no. 1 (2015): 83-113. https://doi.org/10.2752/175174115X14113933306860

Bentley, Ebony.

Bentley, Ebony.